Opinion in lead

COP29: Outcomes and Implications

Prajol Joshi

The COP29 climate summit, also dubbed the finance COP, has ended with an agreement on a new climate finance goal (NCQG) of US$300 billion a year by 2035 to be provided by developed countries to developing countries to fight climate change. Hammered out after an intense two-week negotiation between representatives of 200 countries, the new collective quantified goal (NCQG) is three times more than the existing commitment agreed during COP15 in 2009. The developed countries call it a "huge deal” while most have criticized it for being “disappointing".

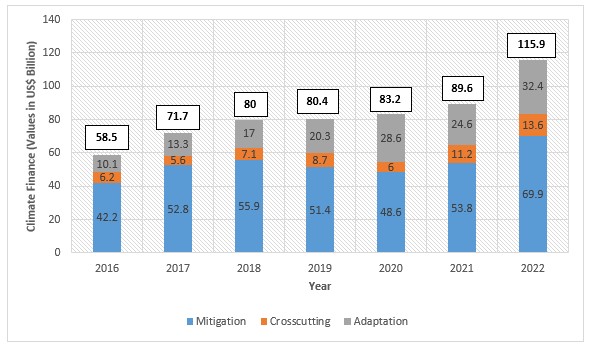

Figure 1: Climate finance provided and mobilized in 2016-2022 per purpose (Values in US$ Billion)

Source: Climate Finance Provided and Mobilized by Developed Countries, OECD

It is estimated that developing countries except China need US$ 1.3 trillion a year to achieve their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) and adaptation goals. So, the new NCQG, despite the general agreement, was criticized by developing countries, activists, and civil society organizations for being inadequate. The representatives from developed countries called the deal historic and a huge win considering rapidly changing geopolitics, mostly following the recent win of Donald Trump in the US presidential election. With Trump as the US President, there is a high chance that the US will pull out of the Paris Agreement again.

The final agreement in COP29 has called for countries to work together and use all public and private sources to meet the necessary climate commitment. This specific mention of private sources in the agreement itself will open up the possibility of bringing in private sources, i.e., private companies and investors. This would further diversify the potential sources but it could mean an additional burden for developing countries, especially LDCs, as private sources usually offer credit on market terms.

A noteworthy outcome from COP29 is on operationalizing Article 6.2 (decentralized emissions trading by countries) and Article 6.4 (a UN-mandated central carbon market) of the Paris Agreement. This was necessary for operationalizing the global carbon market—an essential requirement for over four-fifths of countries to meet their NDC goals. COP26 established a broad rulebook to regulate trading of carbon credits under 6.2 and 6.4 but it was not enough to make the market fully operational. The subsequent COPs failed to further clarify rules to make bilateral arrangements within 6.2 and agree on necessary details to operationalize a central carbon trading system within 6.4. Despite this, there was progress within Articles 6.2 and 6.4 though on a very limited scale. Within 6.2, 91 bilateral agreements have been signed between 56 countries, including one signed between Nepal and Sweden, to begin work on trading carbon credits known as internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs). The COP29 agreement has provided further clarification on how countries will authorize ITMOs and how to track registries and establish mechanisms to further enhance the transparency of transactions.

COP29 has agreed on new methodological standards under the Article 6.4 mechanism known as the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (PACM). These methodological standards are related to the authorization of emissions reductions, the use of the Article 6.4 registry in conjunction with national registries for carbon credits, mechanism by which legacy Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects would be transferred to the new PACM. Both of these positive outcomes from COP29 are expected to further advance the development of the carbon market.

The legacy CDM was established in 2006 under the Kyoto Protocol to help all developing countries meet their emissions reduction targets but the project’s location was highly concentrated (70.36 percent of the projects were from three countries - China, India and Brazil). The entire South Asia region hosted 24.82 percent of the projects in total while India alone contributed almost 92 percent of the South Asian total with 2,882 projects and 3,312 million CER (Certified Emission Reductions) units issued and the remaining 8 percent (255 projects) was hosted by other countries in South Asia. Thus, most developing and least developed countries, including South Asian, were not able to leverage full benefits from the CDM. The main barriers identified were: the limited capacity of these countries to effectively implement the CDM projects, structural constraints and carbon credit prices that either act as drivers or barriers to investments in CDM projects. The Article 6.2 and 6.4 mechanisms thus have to address these barriers to ensure a fully functioning carbon market.

The "Loss and Damage Fund" established and operationalized during earlier COPs received additional commitment of US$85 million during COP29, taking the total commitment to US$731.15 million. The COP29 decided that the disbursement of the fund would start from 2025. Developing countries, during COP29 negotiations, asked to include this fund within the NCQG but developed countries didn’t agree.

South Asia, one of the most vulnerable regions to climate shocks, had a significant presence and involvement during the COP29. India vocally rejected the new NCQG deeming it a "paltry sum" as South Asia alone needs US$200 billion a year and, the region received in total US$92.6 billion between 2002 to 2021 (approximately US$1.25 billion a year), less than one percent of the estimated need. South Asia delegates vigorously flagged the increasing number of climate-related events in the region and the urgent need for more funds to mitigate their effects, and their disappointment with the new NCQG offered by developed countries.

Mr. Joshi is Economist at SAWTEE.. This article was published in Trade, Climate Change and Development Monitor, Volume 21, Issue 11, November 2024.