Opinion in lead

Nepal’s agricultural trade within BIMSTEC

Different trade agreements offer hope of diversifying the export basket and destinations, especially to a net importing country like Nepal, which is desperately trying to expand markets for its agrarian produce. Diversification of markets has become an imperative for Nepal considering the impending graduation from the least developed country (LDC) status and resulting loss of trade preferences. Regional trade arrangements such as the Agreement on South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) and the trade agreement being negotiated under the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectorial Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) could in principle offer a respite in terms of market access. However, as SAFTA has generated very little intra-regional trade, BIMSTEC is often touted as a better alternative given the lower amount of inter-state tensions within it. For Nepal, the question is if BIMSTEC could effectively offer improved trading arrangements with regard to agricultural and food products.

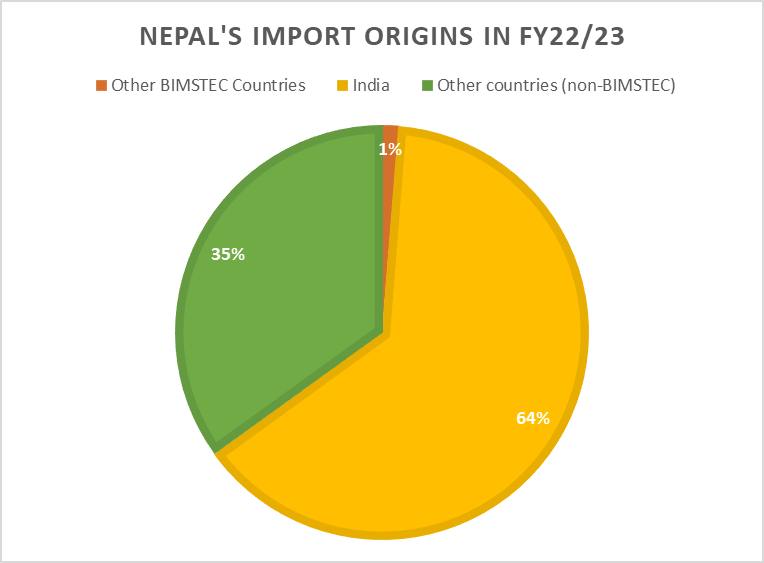

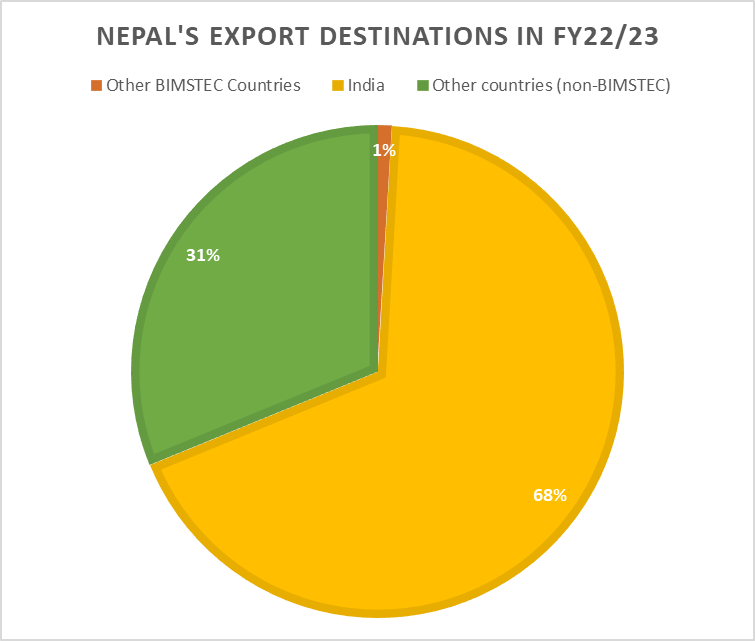

The mixed experience of SAFTA and the slow progress of negotiating the BIMSTEC free trade area (FTA) agreement restrict room for optimism. The Framework Agreement on the BIMSTEC FTA was signed in 2004 and since then there has been limited progress towards materializing it. Nepal’s trade with all other countries in BIMSTEC region is in deficit except with the Maldives. But trade with the Maldives is paltry and erratic. Figure 1 shows Nepal’s overall import situation with BIMSTEC countries in comparison to India and other countries in fiscal year 2022/23. The trend is similar in the previous years. The figure makes it obvious that Nepal’s trade is heavily concentrated with India. For the past decade, annual average trade share of India has been around 67 percent. Last year Nepal imposed import restrictions to preserve foreign exchange reserves, including a ban on imports of bigger cars and other vehicles, so overall trade seems to be in decline. In total BIMSTEC trade, other countries make up merely about one percent of Nepal’s overall imports. The export situation looks quite similar as exports to India make up more than two-thirds of total exports of Nepal (Figure 2).

In terms of agriculture commodity trade, Table 1 considers the products in Harmonized System chapters 1 through 23. It also includes prepared food items such as chips, preserved products, and cereal waste and byproducts that can be used for fodder and animal feeds. In this regard, India also makes up almost 49 percent of total agricultural trade while the share of other countries is minimal. In terms of agricultural product exports, though India comes as the largest, there are other countries such as Bangladesh that have a considerable share.

| Imports (in NPR million) | Exports (in NPR million) | |

|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 2,427.65 | 471.80 |

| Bhutan | 0.07 | 20.67 |

| India | 143,573.60 | 58,893.57 |

| Maldives | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Myanmar | 788.68 | 158.81 |

| Sri Lanka | 65.87 | 3.32 |

| Thailand | 3,226.67 | 9.20 |

| Others | 142,662.28 | 7,949.30 |

More than 40 percent of Nepal’s export earnings come from agricultural products, with tea, cardamom, and ginger being the major export commodities. With India, Nepal’s import of agri products does not look a lot compared to overall trade but Nepal imports staple grains and vegetables from India. Hence, India matters to Nepal for maintaining food security as well. Although exports to Myanmar and Bangladesh show a pretty high concentration of agri products, these are dominated by single products.

There is a lack of diversity in agriculture products traded in the region (Table 2). Except for with India, Nepal’s trade with other BIMSTEC countries is being done in a handful of items. Exports are quite limited. For imports too, except for Thailand, trade with other countries is limited in variety, not only in volume. Myanmar and Bangladesh appear larger in export share of agri items but the trade is limited to red lentils in terms of Bangladesh and herbs with Myanmar. When it comes to India, Nepal is heavily dependent on India for staple food items. Paddy and rice make up the largest imported commodities with about NPR 34 billion worth of imports in the last fiscal year (FY). The value of imports was higher in the previous FY, about NPR 47 billion. But India fixed a quota on paddy export of 600,000 MT for Nepal in October 2022 which might have shown the decline in the official figures. But considering the open border, it is quite likely that the shortfall is being compensated through informal trade. Now that India has imposed export restrictions on non-basmati rice, it needs to be observed how this will be reflected in official figures and also in the food security situation. As for exports to India, they are dominated by soybean and palm oil, which entail a handful of Nepali processors processing crude oil imported from third countries and exporting to India cashing in on the differences in tariffs in the two countries on crude oil imports, the tariff concessions for LDC exports to India under SAFTA, coupled with the lenient rules of origin for such products under SAFTA. Since India has also lowered the tariff on crude edible oil imports, the volume of exports has declined. Interestingly, crude soy oil and palm oil are the biggest imports of Nepal from Thailand. Therefore, in a way this is how regional value chain is working within BIMSTEC.

| Imports | Exports | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value (NPR mil) |

Number of Items | Highest value comm | Value (NPR mil) |

Number of Items | Highest value items | |

| Bangladesh | 2427.65 |

24 | Animal feed inputs, juices | 471.80 | 11 | Red lentils, juices |

| Bhutan | 0.07 | 13 | animals | 20.67 | 7 | Chips, dalmoth etc |

| India | 143,573.60 | 532 | paddy, vegetables, grains | 58,893.57 | 96 | Soybean oil, palm oil, cardamom, juice, tea |

| Maldives | 0.02 | 2 | fish, dalmoth | 0.01 | 1 | Juices |

| Myanmar | 788.68 | 11 | beans and legumes | 158.81 | 2 | Herbs |

| Sri Lanka | 65.87 | 15 | Animal feed inputs | 3.32 | 2 | Flour, green tea |

| Thailand | 3,226.67 |

125 |

crude soyabean and palm oil | 9.20 |

3 | Wheat flour, dog chew |

Just signing a trade treaty will not work wonders with Nepal’s regional trade in agriculture if the existing challenges are not addressed. If BIMSTEC FTA is going to be a reality, the following issues need to be examined carefully for a fruitful collaboration.

Lack of diversification

Nepali agricultural trade is plagued by a lack of diversification—in terms of country as well as commodity. The proximity of the Indian market and its sheer productive capacity and size make India a natural trade partner for Nepal. However, the ease of access for Indian producers has also affected Nepali products’ competitiveness and is considered responsible for the decline of agriculture in Nepal. Policymakers insist that Nepali farmers are not in competition with their Indian counterparts but the real competition is between treasuries of Nepal and India in which Nepal cannot compete with India with regard to subsidies. With other countries, Nepal barely engages in trade in more than a handful of products. It is worth asking: if BIMSTEC FTA happens, will it will lead to diversification of markets and commodities.

Barriers to trade

Agricultural products are the most protected commodities where countries have been imposing outright bans or imposing quotas. For example, India has recently banned non-basmati rice export which has created ripples across the world. Rice and paddy make up about 17 percent of the total agri imports of Nepal and 99 percent of these imports are sourced from India. India had imposed a quota on paddy exports to Nepal for a year beginning in October 2022. The quota ran out in the beginning of August this year. Apparently, there are negotiations going on at the higher level to address this issue. A wheat ban imposed by India has also affected formal imports.

In terms of tariffs, Bangladesh imposes on an average a 25 percent tariff on Nepali agriculture imports. There are many para tariffs such as advance income tax and so on. Nepal also imposes tariff barriers to discourage imports of certain products.

And obviously non-tariff measures, which are in principle measures for safeguarding legitimate interests (e.g., animal, human and plant life and health), are often weaponized to control trade. If issues such as lack of mutually recognized certification and accreditation, and difficulty to access laboratories, persist then having trade agreements will not help at all. To give an example, let us take Nepali export of tomatoes to India. Recently, tomato prices in India reached about INR 300-400 per kilo which were several times cheaper in Nepal. Nepali traders started to export tomatoes to India finally, when the Indian Ministry of Agriculture issued a notice allowing import of tomatoes from Nepal provided they pass certain plant quarantine conditions. This demonstrates that in practice there were restrictions on imports of tomatoes from Nepal—revealed to the public at large when the Indian government relaxed the conditions of imports. Tomatoes are not even in the restricted list under Indian Trade Classification. Yet traders were not able to export tomatoes. Similarly, since cereal exporters of India require export license to export to Nepal, India has a veiled control over what and how much is being exported.

More than SAFTA?

Moreover, since BIMSTEC aspires to introducing an FTA, it needs to be examined how much this arrangement will add to the existing trading mechanism and add value to the existing agriculture trade for member countries. Already, six BIMSTEC countries are members of SAFTA in addition to the bilateral trading arrangements that govern trade while the other two are members of ASEAN. SAFTA has been considered quite ineffective in boosting regional trade. If the sensitive lists under BIMSTEC were to be the same as in SAFTA, what will be the value of the new agreement? Moreover, bilateral agreements seem to supersede regional arrangements. For example, Bangladesh offers better rates to Bhutanese products than Nepali due to a preferential trade agreement between Bangladesh and Bhutan. For any two countries that have signed a preferential/free trade agreement, the benefits for bilateral trade from joining BIMSTEC will be limited. Hence, an important question for the countries in the region for now is whether regional agreements can deliver more than bilateral agreements.

This piece is based on the deliberation made by Ms. Singh at a regional conference on "Agriculture Trade in BIMSTEC: New Opportunities and Way Forward" organized by Research and Information System for Developing Countries (RIS India) and International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) on 17 August 2023 in New Delhi.

Ms Singh is Programme Coordinator at SAWTEE. This article was published in Trade, Climate Change and Development Monitor, Volume 20, Issue 08, August 2023.