Opinion in lead

Public debt in South Asia: Lessons from Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka

Soaring public debt, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, has been in the crosshairs of public debate. South Asia is at the epicenter of the debate. Sri Lanka defaulted for the first time on its sovereign loan and Pakistan is facing severe difficulties in financing its increasing public debt stock. Another South Asian nation, Nepal, while not known for its debt issues, with a relatively modest debt stock, has seen some concern over its precipitously rising public debt. Against this background, three country studies (covering Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) were conducted to assess the state of public debt in these three South Asian nations and to identify what political-economic factors turned their debt sour.

State of public debt

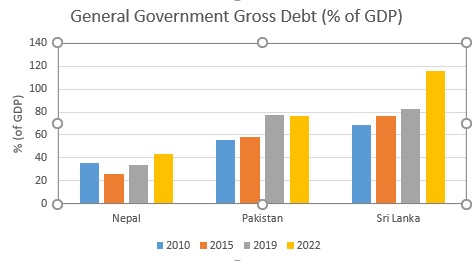

A good starting point is to present the state of public debt in each country. Although government debt has generally seen a significant increase over the years, there is a considerable variation among the countries in their debt-to-GDP ratio (Figure 1). Likewise, notable differences are seen in government revenue and expenditure patterns, and debt-service obligations.

Figure 1: General government gross debt (% of GDP)

The case of Sri Lanka garnered much media coverage as it defaulted on its sovereign debt for the first time in April 2022. It may have come as a surprise to many, as Sri Lanka was seen as an economic success model in South Asia and was widely lauded for its extraordinary social achievements despite a 26-year-long civil war. However, the Sri Lanka study points out that its decades-long structural weaknesses meant that the recipe for a debt disaster was always there. In particular, Sri Lanka ran a persistent budget deficit to “fulfill election pledges and maintain popularity” by relying on foreign loans to finance public investments and social welfare. Even when the debt was skyrocketing, Sri Lanka did not make necessary adjustments and instead opted for counter-intuitive tax-cuts in 2019 (as a fulfillment of an election pledge). This, coupled with the impact of COVID-19 (primarily a grinding halt to tourist inflows, an essential source of Sri Lankan foreign exchange) and policy measures such as a ban on the import of chemical fertilizer (which precipitated a decline in agricultural production and exports) hastened Sri Lanka’s debt default.

Unlike Sri Lanka, Pakistan has not defaulted on its sovereign loans. Still, its severe debt distress manifested in its rapid depletion of foreign exchange reserves (covering less than a month of imports at one point) and its scrambling for International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailouts. While COVID-19, the Russia-Ukraine war, and devastating floods contributed to the crisis, the Pakistan study points out that the main issue is structural. A long history of taking excessive debts to finance development projects (in some cases, without adequate preparation and evaluation), a large public enterprise sector (state-owned enterprises) that pose a significant fiscal burden, and a large web of contingent liabilities mean Pakistan has been running a persistent sizeable fiscal deficit—averaging at around 6.3 percent of GDP between 2000 and 2019.

Nepal’s case is somewhat peculiar as it boasts a relatively low level of public debt and has been consistently found to have a low level of debt distress in debt sustainability analyses. However, it has seen a precipitous rise in its public debt - its public debt stock rose from 25.7 percent of GDP in fiscal year (FY) 2014/15 to 41.5 percent of GDP in 2021/22. While its South Asian peers are trying to emerge from the debt crisis, Nepal is grappling with a different question: is Nepal veering towards unsustainable debt accumulation even when the debt level itself is not yet at a crisis-inducing level? At its core, this entails answering a seemingly simple question: is the public debt stock becoming large enough that servicing it will constrain the fiscal space for growth-and-development-inducing expenditure? However, answering it is not always easy. There is no magic debt sustainability indicator, and despite many attempts by economists to assess when debt becomes counterproductive to growth, there is no consensus on a debt-to-GDP ratio that could be termed unsustainable. While Nepal currently remains at a low risk of debt distress, some trends—the debt service) as a percent of GDP) rose sharply to 4.1 percent in FY 2023, and recurrent expenditures are constantly on the rise but development expenditure targets are not met and development expenditures are of low quality—are worrisome. Hence, against the evidence of a meteoric rise in its debt stock, coupled with a low rate of return on public investments and a myriad of issues in public finance administration, one can reasonably conclude that not all is well with Nepal’s seemingly low level of public debt.

Lessons from the country studies

Investigations into the state of public debt by individual country studies generate important insights, especially for Nepal, which is currently at a low risk of debt distress.

As the country rises in the income ladder, the landscape for external finance changes. Another important insight generated by these individual country studies is that the foreign borrowing landscape changes as a country climbs the income ladder, which could gradually lead the nation toward unsustainable debt accumulation. As a country moves up from low-income to middle-income status, new avenues of foreign capital open. However, some of these new foreign capital sources, such as international sovereign bonds (ISBs) or foreign loans obtained from commercial lenders abroad, are much more expensive because of higher interest rates and lower maturity periods than official development assistance (ODA) loans to which these countries are accustomed. Nepal’s external borrowing remains largely concessionary. However, against its impending LDC graduation (in 2026) and a recent upgradation to lower-middle income status (FY 2021), Nepal would be wise to learn from its South Asian peers and, hence, tread a cautious path, accompanied by institutional reforms.

Geopolitics: myth and reality. Another significant contribution of these individual country studies is that they shed light on the emerging geopolitics surrounding foreign loans, with some observers accusing China of engaging in debt trap diplomacy—burdening developing countries with unsustainable debt. While evidence suggests that foreign loans from China did add to the debt burden in Sri Lanka and Pakistan (Chinese loans, often at higher rates than concessional loans, became an increasing feature of these countries), deeper analysis does not support the debt trap narrative. Debt from other sources significantly surpassed debts from China. The biggest issue with loans from China, rather than its volume and interest rates, seems to be non-transparency.

Importance of country contexts

Besides some common themes surrounding the public debt woes of three South Asian countries, we also see certain peculiarities of each country playing an outsized role in their respective public debt issues, which suggests that country contexts play an essential role in the public debt state of a country. In the case of Sri Lanka, its exceptionally low government revenue contributed significantly to its debt distress. In the case of Pakistan, its extensive public enterprises sector remains a significant contributor to the government’s persistent fiscal deficit. In the case of Nepal, issues in implementing federalism, primarily the duplication of expenditures by the federal and sub-national governments, owing to the lack of clarity on each government’s jurisdiction, have contributed to increased government expenditure. The direct expenditure of the federal government has not subsided even after the devolution of powers and functions to sub-national governments.

Concluding remarks

In crux, these three studies offer insights into how three South Asian countries (Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Nepal), with vastly different levels of debt, face different debt issues. However, amidst this divergence lies a common source of ailment—fiscal mismanagement for short-term political expediency aided by weak public finance administration.

As South Asian nations rise on the development ladder, managing debt becomes paramount for a secure future. Transparency, good governance, and prudent financial management practices are universally important. Implementing these principles across South Asia will ensure a more stable and prosperous path for all.

This article is based on a paper prepared by Mr. Kshitiz Dahal, Senior Research Officer, SAWTEE and Dr. Paras Kharel, Executive Director, SAWTEE, titled “Public Debt in South Asia: Lessons from Three Countries” which synthesizes the country studies on Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Nepal study: Kshitiz Dahal and Paras Kharel. 2023. “Nepal’s Public Debt: Concerns and Drivers.” Kathmandu: South Asia Watch on Trade, Economics and Environment (SAWTEE). Pakistan Study: Ahsan Zia Farooqui, Faisal Bari, Ali Asad Sabir, and Waleed Mehmood. 2023. “The Political Economy of Pakistan’s Debt.” Sri Lanka Study: Yolani Fernando, and Umesh Moramudali. 2023. “The Political Economy of Sri Lanka’s Debt.” The research was supported by The Asia Foundation. The views expressed here are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Asia Foundation.

This article was published in Trade, Climate Change and Development Monitor, Volume 21, Issue 08, August 2024.