Opinion in lead

Tariff burdens Nepal’s merchandise exports to Bangladesh

Despite enormous prospects owing to proximity and close bilateral ties, including a shared free trade agreement, the available evidence shows that Nepal’s export potential to Bangladesh remains severely underutilized.

Economic relations between the two nations have remained under par over the years—for instance, the volume of bilateral trade is relatively low considering the Kakarvitta (Nepal)-Panitanki (India)-Fulbari (India)-Banglabandha (Bangladesh) road corridor that hosts almost all of Nepal-Bangladesh trade is a mere 54 km stretch. Especially, the exports of Nepal to Bangladesh have been consistently decreasing, which is largely dominated by a single product (red lentils), and consists of very few commodities.

Nepal and Bangladesh have a long history of diplomatic and economic relations. In 1972, Nepal and the People’s Republic of Bangladesh established diplomatic relations, making Nepal the seventh country to extend recognition to Bangladesh as an independent country. In addition, to enhance trade, connectivity and bilateral relations, Nepal signed Trade and Payments and Transit Agreements with Bangladesh on April 2, 1976. While the membership of both countries in WTO may have made most of the provisions in the ‘Trade and Payments’ agreement redundant, both the countries are still committed to enhancing trade relations, for instance, through participation in a free trade agreement, and through initiating talks for a bilateral preferential trade agreement (PTA).

Nepal and Bangladesh have seen a steady growth in bilateral relations, with an emphasis on increasing people-to-people connections and promoting trade and economic collaborations. Additionally, both countries collaborate in various regional and global forums. Nepal and Bangladesh are the founding members of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and have contributed immensely in creating this regional platform for cooperation in South Asia. Through SAARC, they are part of the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA), a free trade agreement which provides concessions on customs duties for products exported from the member countries. Similarly, both countries are also active members of sub-regional grouping like the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) and the Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal Initiative (BBIN)—a sub-regional integration project that aims to boost economic cooperation, through enhancing connectivity and transit in the sub-region. The BBIN has made important strides in concluding a motor vehicles agreement among the three partner countries—Bangladesh, India, and Nepal. Once operationalized, passenger and cargo vehicles from Nepal can directly enter Bangladesh through agreed routes and vice-versa, which can have important implications for trading relations.

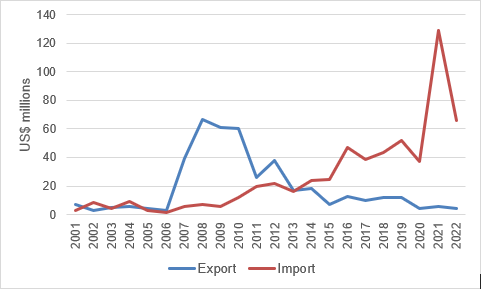

The presence of a host of trade-complementing factors has not resulted in a vibrant Nepal-Bangladesh trade, however. Nepal’s exports to Bangladesh are trivial—in 2022, its exports to Bangladesh amounted to only US$ 4.4 million (Figure 1). Furthermore, Nepal’s exports to Bangladesh, while witnessing a rapid rise in the period 2006–2010—Nepal’s exports to Bangladesh reached a peak of US$ 66.5 million in 2008—has seen a gradual decline since (Figure 1). While Bangladesh’s importance in Nepal’s export rose in the years 2007 to 2010, Nepal’s exports to Bangladesh have remained negligible in Nepal’s global exports throughout most of the history.

Figure 1: Nepal-Bangladesh trade trends

Nepal’s imports from Bangladesh have seen a gradual increase since 2006, with a peak of US$ 128.8 million in 2021. The imports have risen from a low of US$ 1.5 million in 2006 to US$ 65.9 million in 2022 (Figure 1). However, despite a rise in the imports from Bangladesh, it is still negligible in Nepal’s overall imports—Nepal’s imports from Bangladesh are way below 1 percent of its total global imports.

Nepal’s exports to Bangladesh, in addition to being low, show a severe lack of product diversification—the exports are largely concentrated around a single product (lentils). On average, the export of lentils (HS 071340) accounts for about 90 percent of Nepal’s total exports to Bangladesh and Nepal’s top ten exports to Bangladesh account for 98.5 percent of its total exports to Bangladesh.

Tariffs stand out as a significant barrier to exports to Bangladesh. For the potential products identified, the average most-favoured-nation (MFN) custom duties is about 16.6 percent, with many products attracting MFN duty of 25 percent (the median is 25 percent). SAFTA concessions significantly relieve the tariff burden on these products—the average applied duty drops to 9.6 percent once SAFTA concessions are taken into account (the median drops to 5 percent). However, customs duty does not tell the whole story. In addition to customs duties, various duties under the headings of Regulatory Duty (RD), Supplementary Duty (SD), Value Added Tax (VAT), Advance Income Tax (AIT), and Advance Trade VAT (AVAT) are collected at the customs point for imports entering Bangladesh. The total tax incidence increases significantly after the imposition of these ‘other duties and charges’ (ODCs), making it doubly difficult for Nepali exporters to compete with domestic producers. According to a World Bank report, some charges such as regulatory duty (of mostly 3 percent) apply exclusively for imports and hence are unambiguous para-tariffs (ODCs levied solely on imports), but even apparently trade-neutral SD and VAT are para-tariffs in disguise as exemptions are granted for several domestic products. When these para-tariffs are taken into account, the average applied duty (taking into account SAFTA concessions) jumps to 46.7 percent, a significant jump compared to the average customs duty of 9.6 percent. Hence, the high incidence of import taxes on several potential exports from Nepal hinders the export.

Furthermore, in addition to high tariffs and para-tariffs, Nepal’s export prospects are further constrained by the fact that on a few products (including agricultural products of export interest to Nepal, e.g. large cardamoms, ginger, vegetables, fruits and juice, etc.) Bhutan gets duty-free access to Bangladesh. While Bhutan has been getting duty-free facilities for 18 products since 2010, Bhutan gets preferential treatment for additional products after it signed a preferential trade agreement (PTA) with Bangladesh IN 2020 (which came into effect in 2022). In a few products that Nepali exporters believe are potential exports to Bangladesh in significant volumes, Bhutan gets duty-free treatment while Nepali exporters face a high tax burden. This also impedes the export of a few products that have high export potential in Bangladesh.

While the tariff barrier stands out as the biggest barrier, some non-tariff barriers (NTBs) also hinder trade between Bangladesh and Nepal. For instance, our preliminary data collection shows that Nepal’s exports to Bangladesh face a large number of non-tariff measures (NTMs). The presence of NTMs is especially significant for agricultural exports. However, not all NTMs have yet transformed into NTBs; however, there is always a threat that they may gradually be more trade-impeding, especially given that Nepal’s quality infrastructure is weak, and negotiation capacities to resolve NTM issues are not always outstanding. Issues regarding certification and fumigation requirements have appeared time and again, but they have not turned into a significant barrier—addressing these issues, however, can reduce trade costs, and promote exports. Furthermore, there are other issues such as the need for transshipment, subpar customs infrastructure, a significant rise in traffic in the trade corridor, the issue of high reference prices regarding a few exports, and some payment issues. Resolving these issues will decrease trade costs and enhance Nepal’s export potential.

Proactive engagement with Bangladeshi counterparts for better trade facilitation, elimination of NTBS, etc. is needed to address the non-tariff barriers, including procedural obstacles, that pose hurdles to Nepal’s exports to Bangladesh. However, given that the tariff barrier is inarguably the primary barrier, PTA that significantly reduces tax incidence in Nepali exports to Bangladesh could pave the way for greater exports. A closer study of how Bhutan has been able to gain preferential access to several of its products in the Bangladesh market and eventually conduct a trade agreement with Bangladesh could offer some lessons to Nepali negotiators who have been engaged in PTA negotiations with Bangladesh for a few years now.

This article draws on research conducted by Mr. Kshitiz Dahal and Mr. Aayush Poudel, SAWTEE, as part of a project supported by The Asia Foundation. Views are personal. The article is based on an ongoing study by SAWTEE and hence the methodology and results discussed here might undergo further change.

Mr Dahal is Senior Research Officer and Mr Poudel is Research Associate at SAWTEE. This article was published in Trade, Climate Change and Development Monitor, Volume 21, Issue 01, January 2024.